Edinburgh’s Nor Loch | Its surprising dark history

Before the tranquil setting of Edinburgh’s Princes Gardens, there was the fetid stink of Edinburgh’s Nor Loch.

Helping to give rise to Edinburgh’s other name, Auld Reekie, the Nor Loch has a few stories to tell about the city’s past.

Beneath your feet, men and women were ‘ducked’ as warlocks and witches and incestuous lovers discovered as skeletons 200 years after being thrown into the water to drown.

I’ve taken a closer look at Edinburgh’s Nor Loch, from its beginnings as part of the city’s defence, to when this body of water was the ‘go-to’ place for getting rid of Edinburgh’s unwanted.

I know, I know, you don’t come here to the history lesson, rather you come here for the macabre facts that others leave out, but I need to answer a few basic questions about the Nor Loch before I begin.

Feel free to skip ahead if you prefer.

Where Was Edinburgh’s Nor Loch?

Although the Nor Loch in Edinburgh is essentially man-made, its origins began as a natural hollow during Britain’s last Ice Age. The loch covered the marshy ground from the base of Castle Hill to Market Street and the foot of Waverley Station. Today the area is now known as Princes Street Gardens.

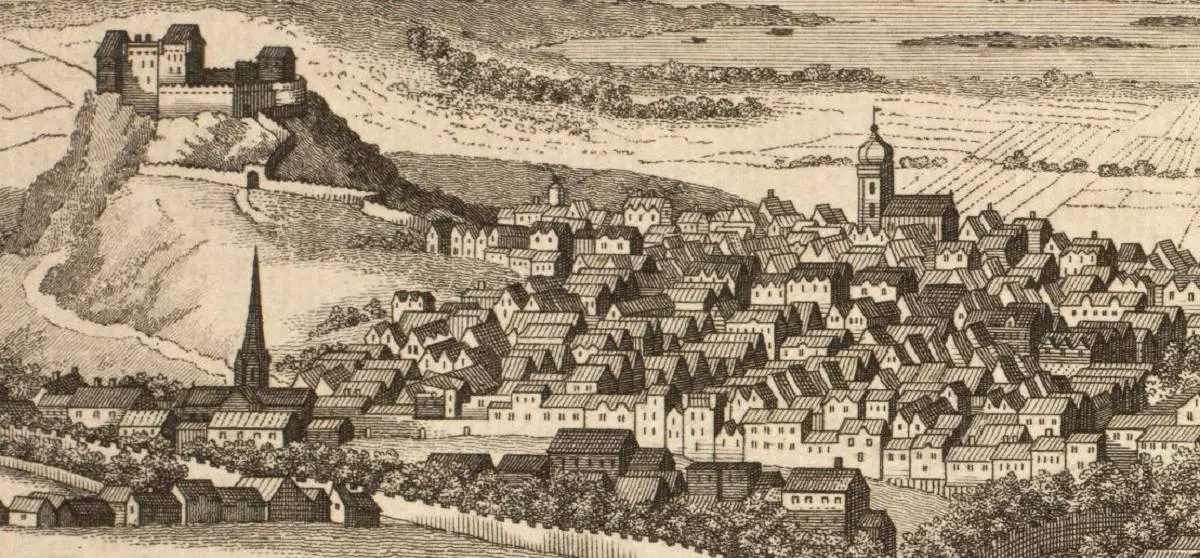

Known as Scotland’s lost loch, the Nor Loch was created in 1460 when King James III recognized that the area could provide a natural defense for what is now the Old Town.

Little did anyone envisage that the city would expand from its 400+ dwellings in the middle of the 14th century to an overcrowded, stinking place with an estimated 50,000 residents some four hundred years later.

The orders from James III to dam up this marshy patch of land and fill it with the waters rising naturally from Margeret’s Well, effectively formed a barricade around the city; blocking everyone and everything in, as well as keeping everyone and everything out.

What Was The Nor Loch Used For?

We need to get one thing straight. The Nor Loch was not built as a specific place for the inhabitants of Edinburgh to throw their waste into, nor was it designed as the town’s sole place to try witches.

So, what was the Nor Loch used for?

The Nor Loch, also known as the North Loch, was built first and foremost, as a defensive barrier to the north of the town against those wishing to invade Edinburgh. By the 17th century, the loch was being used as a waste pit, a place to commit suicide and as a place to try witches and drown criminals.

In 1685, execution by drowning was outlawed in Scotland. Prior to this, the stagnant expanse of water received anything and everything the citizens of Edinburgh decided to throw into it including:

As Hamish Coghill says in his excellent book ‘Lost Edinburgh’ “ For three centuries … the loch was used as a dumping ground for rubbish of all sorts’.

Lucky then that the water from the Loch was never used as drinking water, residents getting their water from The Wellhouse Tower.

Why & When Was The Nor Loch Drained?

Edinburgh’s Nor Loch was drained to allow for the construction of the North Bridge at the eastern end of the site in 1764 as part of the development of Edinburgh’s New Town. Between 1813-1820 the western end of the loch was drained which eventually led to the development of Princes Street Gardens.

The stench created by the detritus dumped into the Nor Loch gave rise to the upper classes pushing for its drainage by 1754. They would have a further ten years of suffering before the plug was pulled on one of the town’s most well known locations and the air in Auld Reekie would finally improve.

A breakdown of the drainage works was as follows:

With nowhere to expand, the town of Edinburgh had grown up and down instead of out. It’s Nor Loch hindering the city’s very growth.

Underground worlds developed as tenements as high as the eye could see, nigh on butted together as their roofs reached further into the sky. The most famous of all Edinburgh’s Closes is probably Mary King’s Close.

Try as I might I cannot find any conclusive evidence as to how the loch was drained. I was hoping to give you some 18th-century construction techniques, but alas, Google has failed me.

What Is The Mound In Edinburgh?

The Mound to the west of Edinburgh’s Princes Street Gardens was made from the rubble created when digging foundations for the New Town. Construction work started in 1763 and The Mound was formed between 1781-1880.

If you’ve ever decided to walk up from Princes St to the Royal Mile, chances are you’ve encountered The Mound first-hand.

This sometimes-punishing slog is best tackled at a steady pace whichever route you take – directly up the steps past the National Gallery or via the more leisurely sweep up The Mound and onto North Bank Street.

I find a drink on the Royal Mile a fantastic reward whichever route you’ve come. I think, depending on your route, Deacon Brodies could be one of the first that I would recommend.

Were Witches Punished In the Nor Loch?

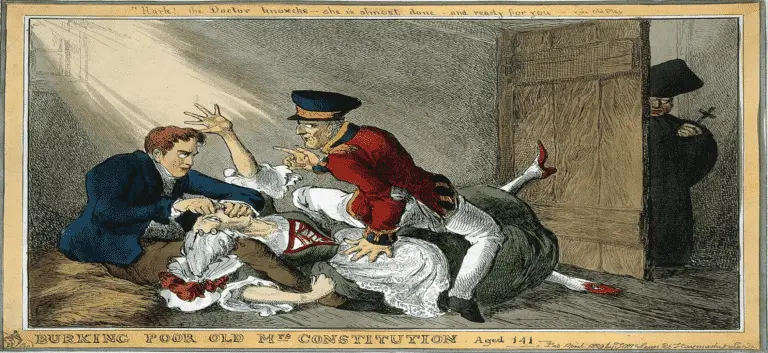

It is estimated that more than 300 men and women were subjected to ‘witch ducking’ at Edinburgh’s Nor Loch, suspected of being warlocks and witches. A record eleven women were drowned in 1624 because of this supposed crime.

The Ducking Stool

In a test that to modern eyes was always designed to fail, women would have their thumbs and toes tied together before being put on a ducking stool and subjected to the icy waters, letting the loch decide their fate.

If they sank and died then to 17th-century eyes, the women were clearly innocent and free from any evil spirits. Not a very good outcome for the accused if they were no longer alive to enjoy their freedom.

If however, the women ‘denied all sense’ and didn’t sink, then a further punishment awaited them.

Burning At The Stake

They would be dragged from the loch and taken to Castle Hill, strangled and then burnt at the stake in front of a large crowd.

One particular incident involved Janet Douglas, Lady of Glamis who was burnt as a witch on Castle Hill now the esplanade in July 1537.

Known as the Grey Lady of Edinburgh Castle, her sixteen-year-old son was forced to watch, she now haunts the castle hallways as well as her former home Glamis Castle.

The Witches Well

If you do take a tour of Edinburgh Castle, then just keep an eye out for The Witches Well as you walk up the esplanade.

Commissioned in 1894, the well stands as a tribute to the women and men who suffered during this period.

If you’re interested in reading further on this topic then The University of Edinburgh has a page on their website ‘The Survey of Scottish Witchcraft’.

Discovering Skeletons In The Nor Loch

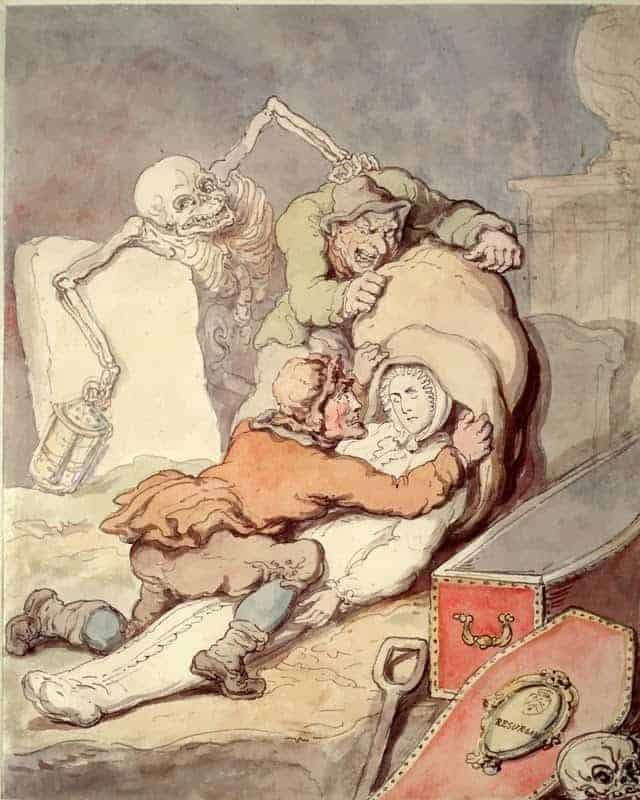

Construction work for Edinburgh’s Waverley Station revealed numerous human bones over the years and infant skeletons too have been found further along the banks of the Nor Loch. But the most famous discovery of a human skeleton was made in 1820, near the site of the Wellhouse Tower.

During the excavation work, Edinburgh Lawyer James Skene, also a friend of Sir Walter Scott, thought it wise to pay a visit to the Tower, hoping to find some relics that could perhaps shed additional light on Edinburgh’s history.

Initially, he was disappointed, finding only a ‘few coins to offer to the Society’ – that’s the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (2:1822). But as the digging progressed, workers made their way round to a ‘scrambling stair’.

A skull, which ‘from the thickness of the bones, the proprietor seems to have had a pretty substantial head’ had shattered into pieces upon hitting the bottom step. But then a discovery was made in the Spring of 1820.

Discovery Of Three Human Skeletons In the Nor Loch

In the Spring of 1820, as a trench was being dug to the eastern side of the tower, a ‘large coffin of thick fir deals, in which there were three skeletons’ was found.

Unfortunately, Skene was too late to stop the workmen from opening the coffin which sounds as though it immediately fell apart. But they did confirm that they gathered up all of the bones, ‘guv’, and had reburied them where they’d found them.

Skene’s initial thoughts seem to turn to witchcraft rather than the case of George Sinclair in 1628 to which he later turned.

The workmen, however, had other ideas. The body in the middle was clearly that of a tall man they told Skene, the others, women ‘because they were shorter and very broad about the flanks’.

Tried & Drowned For Incest in 1628

Openly admitting incest with his two sisters, George Sinclair and his siblings were found guilty in 1627 and sentenced to be executed by drowning in the Nor Loch.

The workmen who had made the discovery, not Skene himself which is often cited, surmised incorrectly that there were three skeletons in the coffin that day for investigations carried out in the 19th century confirmed the existence of only two.

History has dictated that the man was always George Sinclair. The other skeleton however is thought to belong to the older of the two sisters, the younger of George’s sisters believed to have been spared.